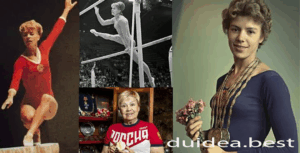

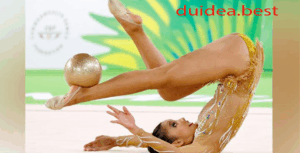

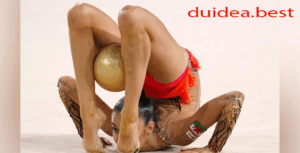

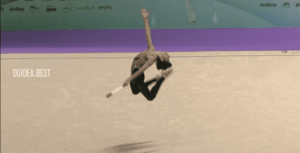

Sutji Memulai Senam Ritmik Sejak Usia Delapan Tahun: Perjalanan dan Prestasi

Pendahuluan Sutji Memulai Senam Ritmik adalah salah satu cabang olahraga yang menggabungkan keindahan seni, kelenturan,…

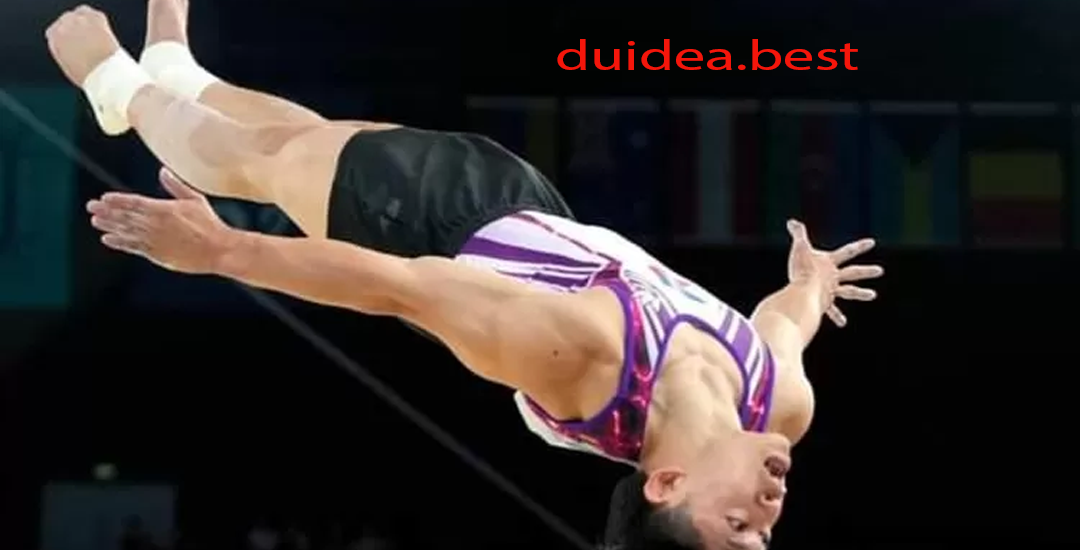

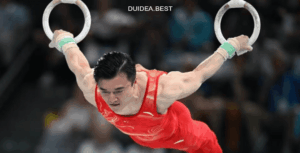

Carlos Yulo: Atlet Senam Lantai Filipina yang Membanggakan di Ajang Olimpiade

Pendahuluan Carlos Yulo Dalam dunia senam internasional, nama Carlos Yulo mulai dikenal luas sejak…

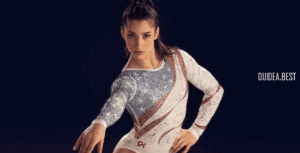

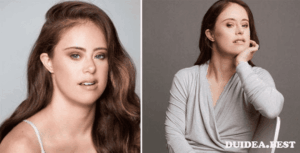

Sunisa Lee: Kisah Inspiratif Pesenam Amerika Serikat yang Raih Medali Emas di Olimpiade

Pendahuluan Sunisa Lee Di tengah gemuruh panggung Olimpiade Tokyo 2020, seorang pesenam muda asal Amerika…

Stephen Nedoroscik dan Clark Kent: Dua Identitas, Satu Pribadi

Pendahuluan Stephen Nedoroscik Dalam dunia yang penuh dengan tokoh superhero, identitas rahasia menjadi salah satu…

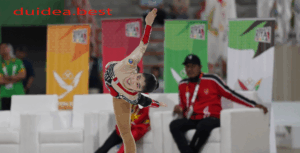

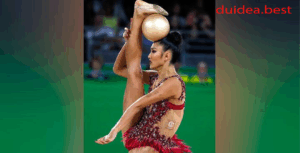

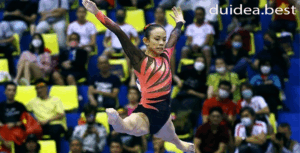

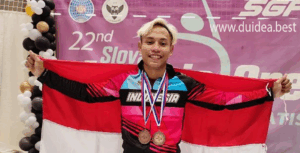

Shalfa Avrila Raih Medali Perunggu di Kejuaraan ASEAN Schol di Singapura

Pendahuluan Shalfa Avrila Pada ajang bergengsi Kejuaraan ASEAN Schol yang berlangsung di Singapura, nama Shalfa…

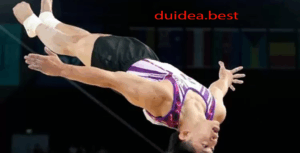

Simone Biles Tampil Memukau di Nomor Senam Lantai pada Seleksi Tim Olimpiade AS di Target Center

Pendahuluan Simone Biles Tampil Memukau Pada ajang seleksi tim Olimpiade AS yang berlangsung di Target…

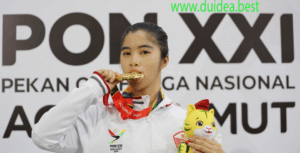

Umi Sri Haryani, Atlet Senam Lampung, Beraksi Gemilang di Final Senam Aerobik Perorangan Putri

Pendahuluan Umi Sri Haryani Pada Pekan Olahraga Nasional (PON) XX Papua yang digelar di Tanah…

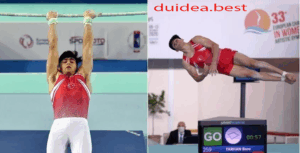

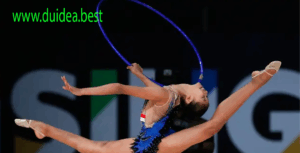

Atlet Bora Tarhan dan Mert Efe Kilicer Meraih Medali di Kejuaraan Internasional

Pendahuluan Atlet Bora Tarhan Pada kejuaraan internasional terbaru, dua atlet berbakat dari Turki, Bora Tarhan…

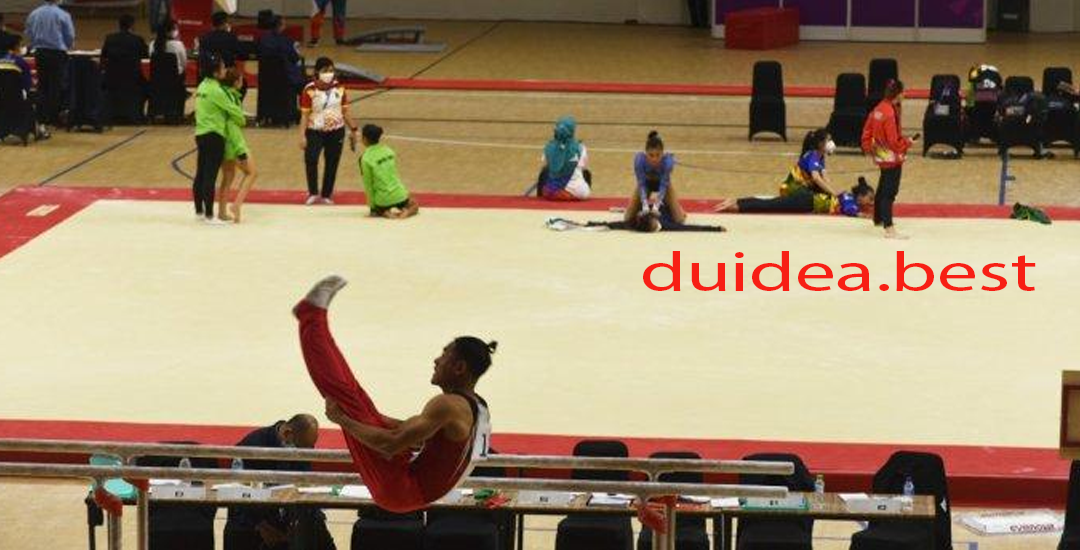

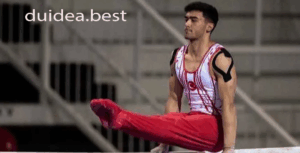

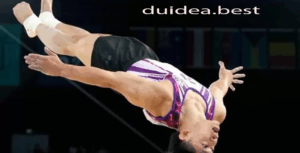

Meiyusi Ade Putra dan Keahliannya dalam Nomor Palang Sejajar dan Kuda Pelana Artistik Putra

Pendahuluan Meiyusi Ade Putra Dalam dunia olahraga senam artistik, setiap atlet memiliki keunggulan dan keunikan…

Sunisa Lee: Pesenam Putri Amerika Serikat yang Memukau di Olimpiade dengan Keanggunan

Pendahuluan Sunisa Lee panggung bagi banyak atlet dari seluruh dunia untuk menunjukkan bakat dan perjuangan…