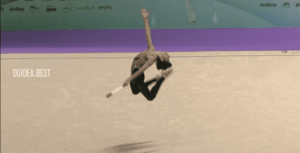

Senam Trampolin: Olahraga Akrobatik yang Menggabungkan Keseimbangan dan Kecepatan

Pendahuluan Senam trampolin adalah salah satu cabang olahraga akrobatik yang memadukan keindahan gerakan, kekuatan, keseimbangan,…

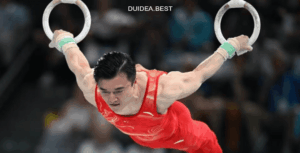

Fan Yilin: Bintang Gemilang dari Dunia Senam Artistik China

Pendahuluan Fan Yilin: Bintang Gemilang dari Dunia Senam Artistik China. Fan Yilin adalah salah satu…

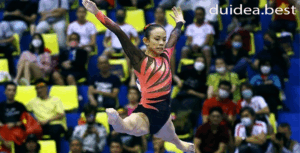

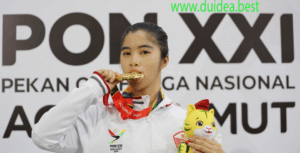

Atlet Senam Aerobik DKI Jakarta, Krischayani Kurniawan, Raih Medali Emas di PON

Pendahuluan Atlet Senam Aerobik DKI Jakarta Dalam ajang Pekan Olahraga Nasional (PON) terbaru, dunia senam…

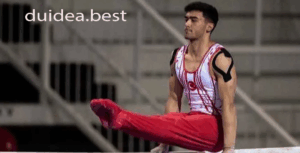

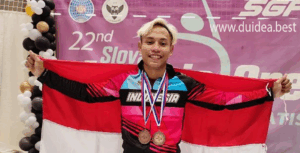

Mert Efe Kilicer: Atlet Berbakat yang Mengklaim Medali Perak dan Perunggu

Pendahuluan Mert Efe Kilicer Dalam dunia olahraga internasional, keberhasilan atlet tidak hanya diukur dari medali…

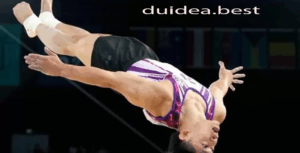

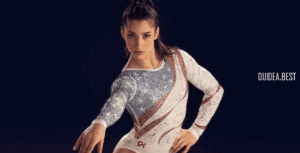

Jutta Verkest, Peserta dari Belgia, Tampil Memukau di Babak Kualifikasi Nomor Balok

Pendahuluan Jutta Verkest Pada ajang Kejuaraan Dunia Senam Artistik yang berlangsung baru-baru ini, salah satu…

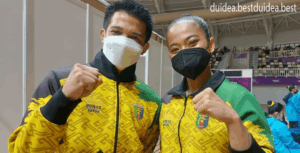

Denda Firmansyah dan Umi Sri Haryani, Atlet Aerobik Asal Lampung yang Sabet Medali Emas

Pendahuluan Denda Firmansyah dan Umi Sri Haryani Dua atlet aerobik asal Lampung, Denda Firmansyah dan…

Giulia Steingruber: Atlet Senam Putri Swiss yang Membanggakan Dunia

Pendahuluan Giulia Steingruber adalah nama besar dalam dunia senam artistik, terutama bagi Swiss yang selama…

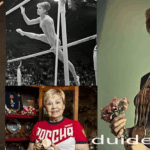

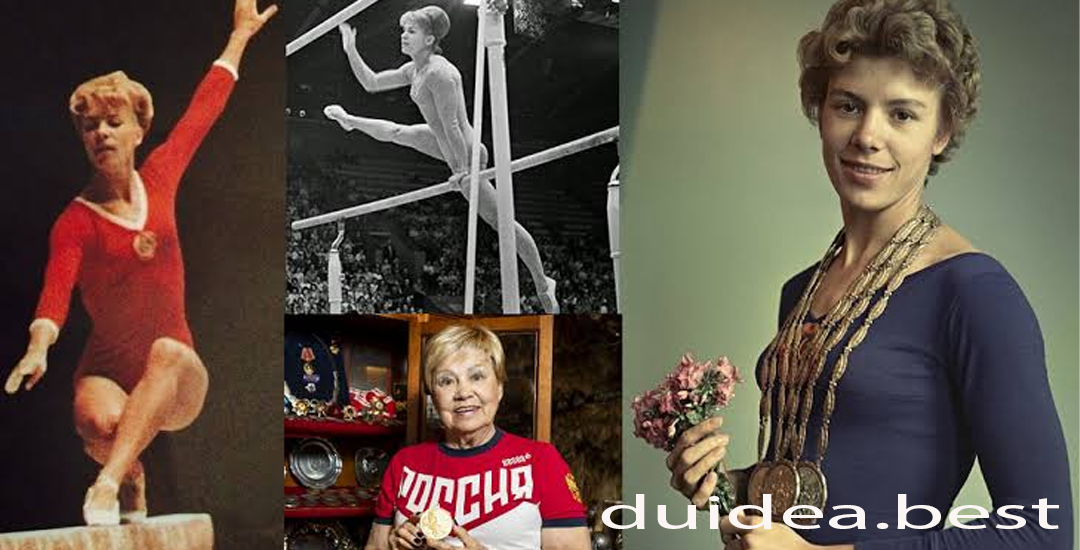

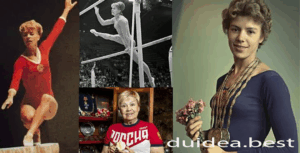

Larisa Latynina: Legenda Gimnastik Soviet dan Pemegang Rekor Tersukses dalam Sejarah

Pendahuluan Larisa Aleksandrovna Latynina adalah salah satu tokoh paling berpengaruh dan legendaris dalam dunia olahraga,…

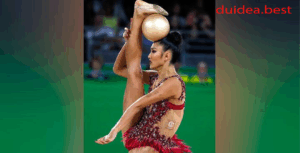

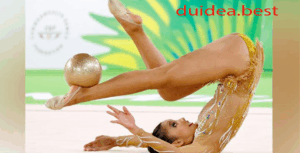

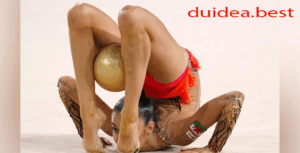

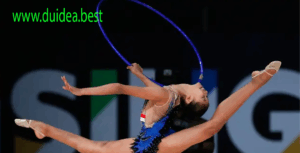

Pesenam Nasional Rifda Irfanaluthfi Persiapan Maksimal Sebelum Melakukan Rutin Gerakan Alat

Pendahuluan Pesenam Nasional Rifda Irfanaluthfi Dalam dunia olahraga senam, persiapan matang adalah kunci utama untuk…

Shoko Miyata Dikeluarkan dari Olimpiade Paris: Kontroversi dan Dampaknya bagi Tim Senam

Pendahuluan Shoko Miyata Berita mengejutkan datang dari dunia olahraga saat Shoko Miyata, kapten tim senam…